The Monks' Electric Fee

- Sep 10, 2023

- 3 min read

Many people have heard from The Lonely Planet about Bangkok's street food in Buddhist Temples. But not many people know the going rate the monks are charging for 'hook-up fees' for these street sellers. These hook-up fees are independent of the utility company's electric rate -- usually with a mark-up of 2 to 3 times the actual rate. As of 2016, the typical mark-up electricity rate is 50 baht/stall/night. Assuming the vendors sell every night, then the monks could collect around 1,500 baht/stall/mo. With over 100 stalls, the monks can get roughly 150,000 baht per month -- an executive sum from re-selling electricity alone, independent of space rental fees.

Let's look at the street vendor's typical electric demand. The typical vendor's incandescent bulb uses about 0.06 KW of power per bulb. Assuming that each stall runs about 8 hours per night and has 10 bulbs, then you got 4.8 KWh/stall/night. In 2016, the electric rate is about 4 Baht/KWh, so the monk's electric cost should be close to 19.2 Baht/stall/night. Since the monks resell their electricity at the rate of 50 baht per stall/night, this translate to 2.6 times the utility's electric fee. (Food vendors usually cooked with their own gas stoves)

Yet this type of micro-grid or "sub-grid" electricity trade is common in all types of street bazaars outside the temple, including street bazaars next to supermarket's ground like Tesco Hypermarket or street vendors next to shopping malls. Electric lines are strung directly from the main building to the stalls area in series. The same is true in slum housing settlement; people with connection to local politicians got their legal addresses -- and access to electricity -- can sell electricity to other squatters at 3 times the going rate. This is true even in apartment buildings in Bangkok; the electricity rates are usually resold at a much higher rate.

Electric lines strung across the walkway from a supermarket to power the street bazaar. While this type of electricity reselling is prohibited in other parts of the world such as California, for example, such practice in Bangkok allowed for easy plug-and-play of new businesses and housing throughout the city despite potential safety hazards.

Bangkok’s street vendors collectively created an instant city of food and service. They are a tool for ordinary citizens in ‘hacking’ -- and surviving -- a combination of low wage economy and bad infrastructure system. The minimum wage in Thailand is $10 per day, while most sit-down restaurants and eateries cost at least $5 per meal. Most office workers and professionals are dependent on street vendors for their breakfast, lunch, and dinner.

The lack of time is the number one issue in the life of Bangkok workers. As of 2015, automobile traffic moves at an average speed of around 15 km/hour, according to the city’s department of transportation. One cannot plan more than 2 meetings per day in different location with any certainty. As a result, free time becomes a luxury.

Bangkok streets accounted for as little as 8% of the city area. Large superblocks of private land have taken over much of the city fabric, leaving little room for streets and public spaces.

In Manhattan, streets take up of around 36% of the city core area. In Hong Kong, the streets take up 34%, followed by 29% in Tokyo. (UN Habitat)

A combination of low wages and the lack of time created a DNA of a city that generated an urban form of instant kiosks and cheap food.

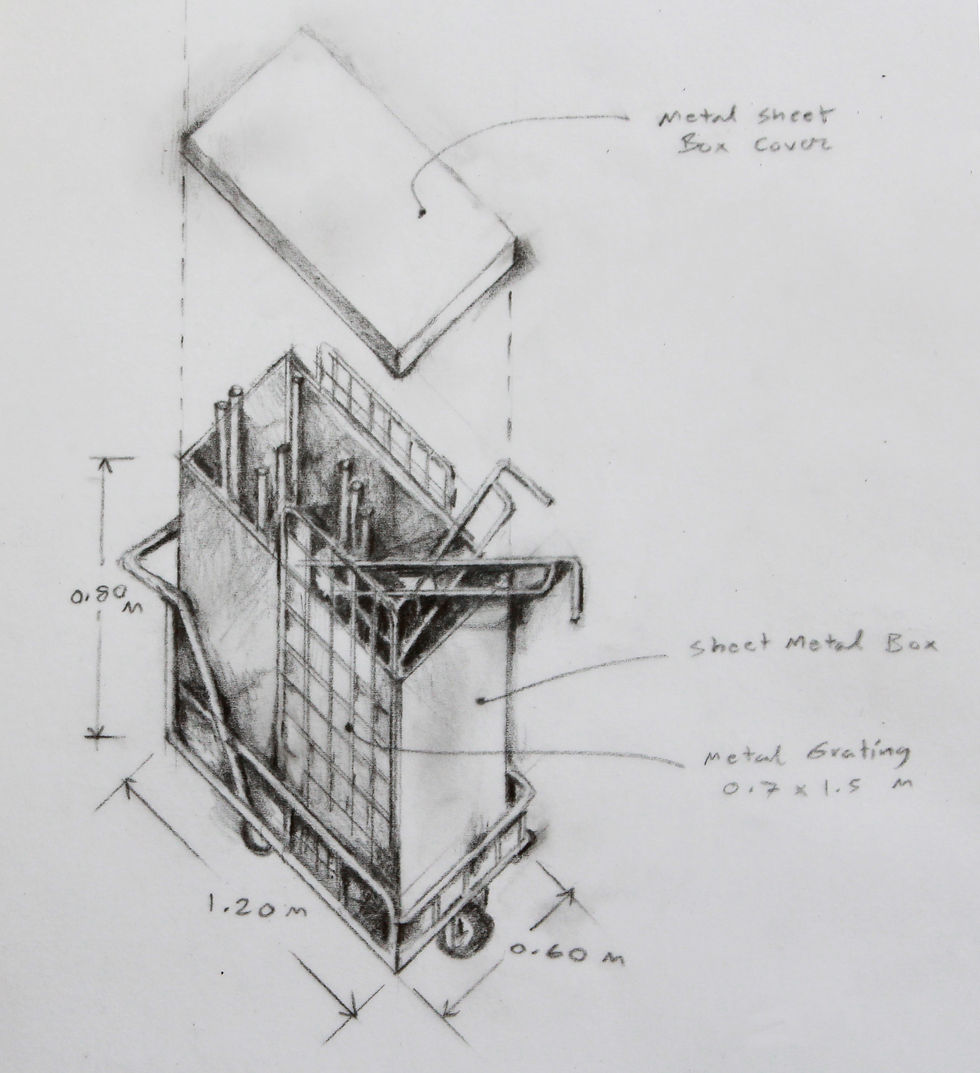

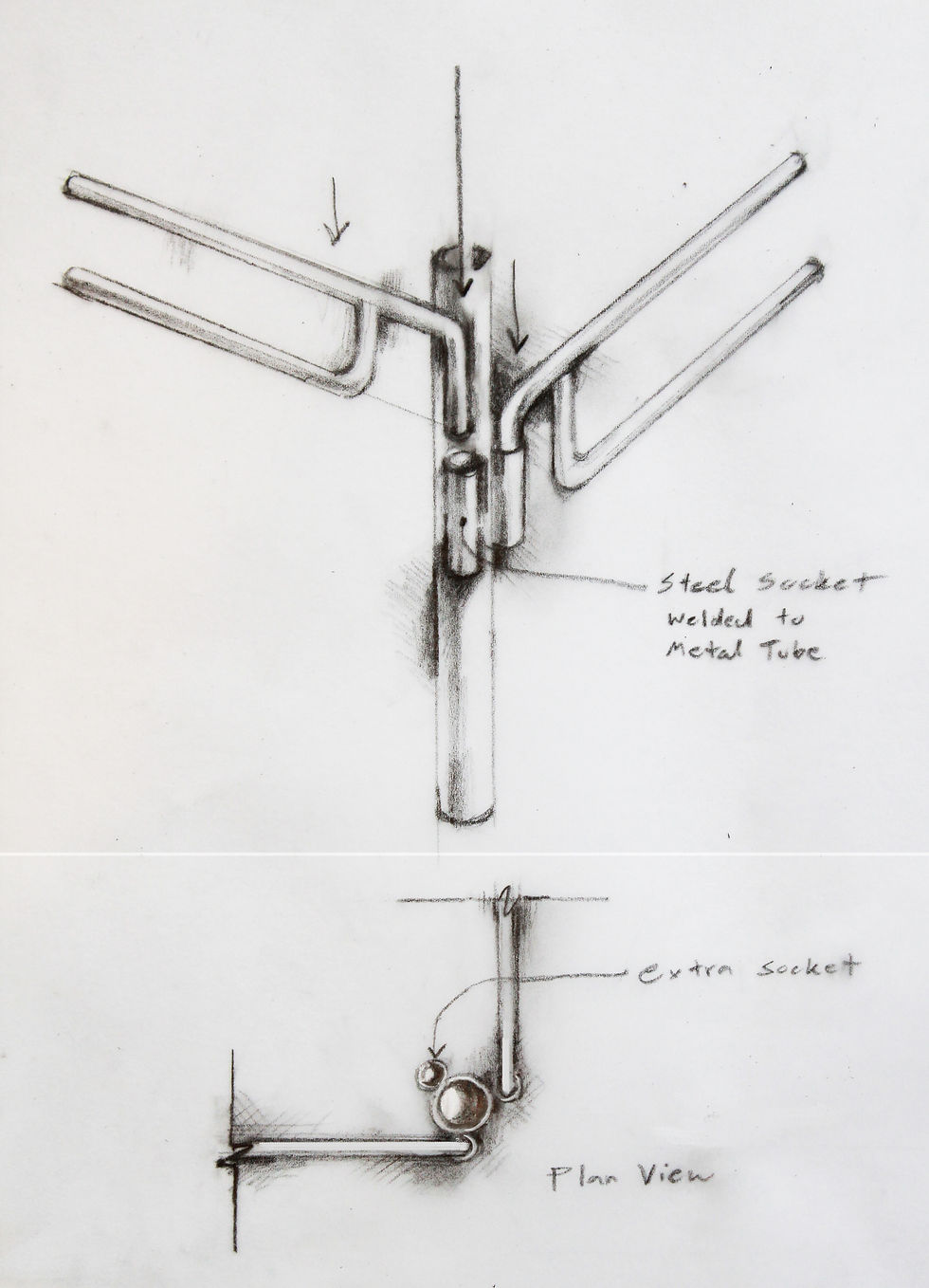

Over time, people collectively create a modular system of street carts that could be transformed into food kiosks. The system consists of steel tubes with some variation of connectors. Once arrived at the site, they could be folded up within an hour.

The street carts that hold these modular steel structures are packed into a steel box; they could be carted away when the police arrived. However, the sellers usually pay a monthly ‘rent’ to the police officers so as to reserve their position on the city’s sidewalks.

Comments